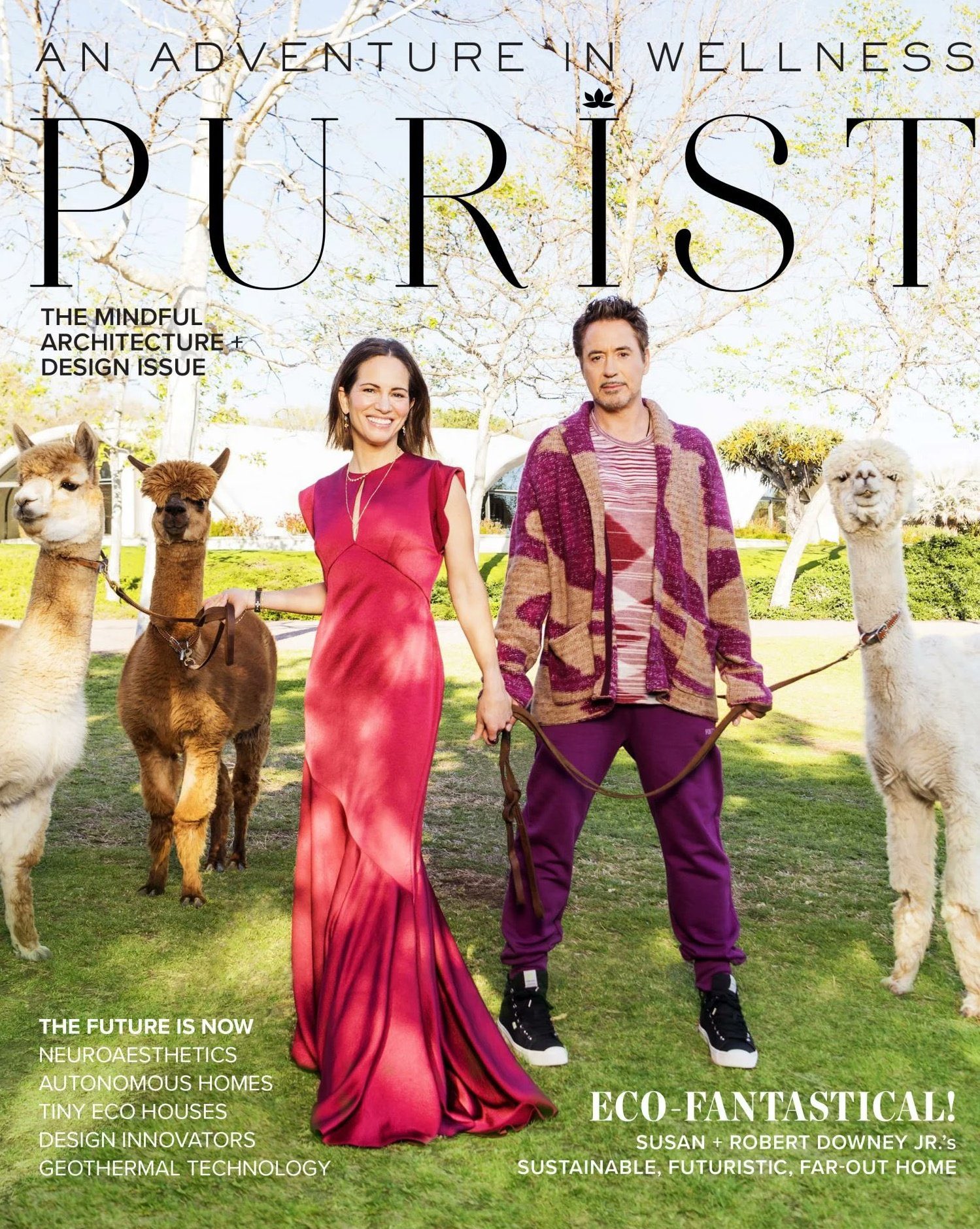

Back To The Future: Susan + Robert Downey Jr.’s Sustainable Sanctuary

A visit to the Downeys’ new reduced-carbon-footprint, energy-efficient Malibu Binishell home of tomorrow.

Photography by Andrew Macpherson; Styling by Jeanne Yang; Hair/Makeup by Davy Newkirk.

Interview by Alastair Gordon, Portraits by Andrew Macpherson

Robert Downey Jr. (actor, entrepreneur) and his wife Susan (née Levin, a successful movie producer in her own right) are co-founders of the Footprint Coalition, an organization that brings awareness, leverages VC capital and provides grants toward the scaling of sustainable technology. Part of their inspiration has been the development of a 7-acre homestead in Malibu, California, where cutting-edge wind turbines and solar-generated water systems offset the energy consumption of multiple structures. There’s a preexisting house, built in the 1970s, comfortably conventional with gray siding and multiple gables. And the Binishell: a bold, undulating experiment in architectural sustainability. Planned as a whimsical family guesthouse, it is becoming the basis for a larger lifestyle shift they are presently in the midst of. Robert and Susan have kindly invited Purist to explore the future of eco-friendly home building and share some of their unique spatial experiences.

Alastair Gordon: From the air, the Binishell resembles a three-headed turtle shell that’s been bleached in the sun. There’s not a straight line or right angle in sight.

Robert Downey Jr.: Duly noted.

AG: When did you buy the property in Malibu?

Susan Downey: First things first, we should partly credit you for embracing home design innovation. Your book Spaced Out was one of several sources of courage. We bought the property in 2009 as three contiguous parcels. We did very little to the main house. Our first designer was Robert Clydesdale. We love him and his elevated, eclectic taste. Three years later, when we were thinking of building an ancillary structure, he came to us excitedly and said, “I’m telling you- Nicolò Bini is the right architect.”

AG: Did you interview other architects before settling on Nicolò?

RDJ: Several. None of whom, obviously, proposed anything like Nic’s method. He introduced us to the technology that his father, Dante Bini, had developed in Italy in the late ’60s. The outer form is created using large inflatable bladders that are covered in concrete.

AG: The design is the same free-form as those alternative structures of the 1960s and 1970s: geodesic domes, biomorphic shelters and womb rooms that the hippie counterculture embraced as a revolt against the tyranny of the same square and straight lines. Even though it’s kind of retro, your house seems like a radical design for today. Were you inspired by that earlier period of experimentation or was it something else?

SD: We were open to embracing an unconventional approach.

RDJ: Nic is so passionate and dynamic—his enthusiasm was infectious.

SD: Assembling a group to foster an artistic vision infused with ingenuity that results in something unique is a goal we are quite familiar with, given our day jobs.

RDJ: It was a learning curve in a new arena. Like many “passion projects” it wound up being a seven-year endeavor. It was Bini’s overall vision that we backed. Mike Grosswendt (All Coast Construction) is another hero of the story: completing the shell exterior, the entirety of the interiors, getting it done within budget, while meeting every required approval of the city and coastal commission. He never balked at the notion of building within a realm devoid of right angles. Ben Goodman (Goodman Architecture) did the interiors. He and Mike set up our interior designer Joe Nahem (Fox-Nahem Design) to have maximal leeway with the elements of material, palette, taste etc.

SD: Eventually we ran out of problems to solve, and we could enjoy the finer design elements with Joe, whom we’d become close with after Fox-Nahem reimagined our East Hampton residence in 2017.

AG: The pale-blue doorways are eccentrically shaped to fit into the cave-like openings with a single pivoting hinge and porthole windows. Ovoid skylights were punched through the ceiling wherever you needed natural light. Did every opening—every door and window—have to be custom fit?

RDJ: More often than not, we did what we had to do to stay within budget. In many instances, we were forced to focus on the cheapest, greenest solution.

AG: Your house evokes the traditions of 20th-century utopian design, but there’s also something cartoonish about the convergence between German Expressionism (I think of Erich Mendelsohn), Hobbit huts and Teletubbies barrows—especially in those thick-lipped portals that appear to gape and pout in exaggerated pantomime.

SD: That was really one of the balancing tricks: how to find items that worked in harmony with this unique structure without falling into parody. Never gilding the lily or having it look like Fred Flintstone’s house.

AG: Well, it may not be parody, as you say, but you’re certainly surfing along the edge of something that could be considered ironic. Can you walk us through some of the interior spaces?

RDJ: Right through the entry door there’s this architectural bead screen. It’s the first thing you see when you walk in.

AG: It looks like it’s made from gray and brown ceramic elements.

SD: Like Robert was just saying…budget. We opted out of the ceramic price point. These are custom-designed fiberglass beads by Fox-Nahem that Joe Nahem commissioned from an artisan in Mexico.

AG: Various rooms unfold to the east and west from the central passageway. They are more like cellular pods or the chambers of a nautilus shell than conventional rooms. Behind the dining area are two guest rooms with a terrace and some kind of bizarre dystopian fountain that features a punctured oil drum and the head of a distressed-looking Mickey Mouse who appears to be wearing a gas mask.

RDJ: The fountain is by the exceptional LA-based artist Bill Barminski. It’s a bit of an ironic tribute to Walt Disney’s contribution to Cold War gas mask designs.

AG: Often, you see an experimental house and it’s so exciting on the outside, but then you go inside and it’s a bummer. In your case, the choices seem just right: eclectic, personal and somehow in tune with the cellular nature of the interior layout. I’m thinking of that carnivorous-looking couch with gray-and-pink upholstery and bulbous, knuckle-shaped padding in the living room, and also the mushrooming lamps made from stretched translucent fabric.

SD: We’re fine with a bit of whimsy. There was a level of trust built through the project with Joe in East Hampton, knowing we could play with crazy shapes and colors that would sit well in the space and not become chaotic. To ground things, about 80% of the pieces in the living room, dining room and bedrooms, are Roche Bobois.

RDJ: Roche Bobois has a qualitative assessment tool called Eco8. A new criteria for furniture manufacturers. We’re big fans.

SD: Similar to inside, we kept the outdoor furniture to a single designer—Paola Lenti.

AG: To the west of the entry axis is a family entertainment center or screening room.

SD: Ben Goodman proposed we build a structure within a structure, a self-contained floating box that never touches the interior ceiling of the shell.

RDJ: I requested a wildly complex folding garage door with a 2-horsepower motor. We needed a flex space that could operate both as a theater or an extension of the living room…kids.

AG: Farther to the west, in front of the playroom, is a den? I’m talking about the sunken space with an ovoid shaped window, illuminating a roughly textured wall.

SD: Robert wanted to play with different elevations within the house. Here, you step down into that space that operates like a family den.

AG: So you call it the den?

RDJ: We call it “Susan’s Office.” The textured wall is made from strips of recycled wood. Again, Joe Nahem.

AG: To me, the most signature interior space is the playroom itself. Softly contoured seating follows the wavering perimeter of the room, but the centerpiece is this wonderful elevated nest, a wicker pod of some sort, in which family members––or maybe only a single person––can crawl inside and hang in a state of suspended contemplation.

RDJ: This awesome South African designer Porky Hefer calls it a “Humanest.” It’s made from woven kooboo cane, rope and leather.

The hanging nest in the playroom from South African designer Porky Hefer is called a “‘Humanest,’ made from woven kooboo cane, rope and leather,” says Robert Downey Jr.

SD: I love that it’s equal parts sculpture and relaxation nook. I remember when Joe took Robert to Jeff Lincoln’s design collective in Southampton (Jeff Lincoln Art & Design) he…

RDJ: …I climbed in it and said, “We need this for Malibu.”

SD: Mike, the builder, was like, “How the hell am I supposed to hang it? It’ll pull the ceiling down.” He ended up submerging a circular, hook-shaped steel bar into the concrete foundation.

RDJ: That’s how!

AG: To me, it feels oddly like a metaphor for this entire period of quarantine and isolation. The warm, hand-plaited feeling of this room is further enhanced by a stuffed alligator that lies on the floor, as well as a series of unusual ceiling lights. Are they basket-type lamps from a single designer?

RDJ: Joe really is a design master, so when he said, “I’m gonna select a dozen fair-trade baskets, invert them, use multi colored electrical wires and make the playroom ceiling a feature. Any questions?”

SD: We said, “Nope, cool!”

AG: Moving back outside, the landscaping helps to magnify the object-like presence of the Binishell. Plantings are casual and natural without looking self-conscious or overwrought.

RDJ: Any structure is only as good as the landscape architecture that surrounds it. Ana Saavedra is a rockstar.

SD: She’s one of those people you talk to for five seconds and realize they’re an expert. Whether framing the entry, building knolls and mounds, making the fountain enclosure feel private, she had a creative solution for everything. She’s also big on minimizing water usage by choosing drought-resistant plantings, trees, shrubs and grasses.

AG: Two-part question. What are those solar panels that make water? And where are the wind turbines located?

RDJ: A) the Source Hydropanels extract clean, premium-quality drinking water from the air, and we put them dead in the middle of an open field area. Because we want folks to get used to seeing these kinds of innovative contraptions as they begin to proliferate. And B) I spoke too soon, the Vertical Access Wind Turbines (Terra Sustainable Technologies) are en route from the Netherlands and will be placed where they tested for optimum wind conditions. They’ll offset a nice percentage of our Binishell’s grid dependency.

SD: They’re beautiful. Like a sculptural installation.

AG: As a final question, I have to know about your animal collective because I have this lingering image of Robert weaving alpaca wool, making his own sweaters. How did the Dr. Dolittle menagerie begin?

RDJ: Back in 2010 we got two pygmy goats and several horses as gifts, then I asked Su if we could adopt four alpacas, and she said—yes.

SD: I didn’t say no. Which he took as yes. Same for the Kunekune pigs.

RDJ: Then we got belted Galloway cows and 26 chickens. Which she agreed to.

SD: Not quite. I agreed only to the subsequent rescue goats after the cows and chickens magically arrived. I did, however, agree to Jasper and Margrit, the Lionhead rabbits.

AG: Noah’s Ark… What’s the total count up to this point?

RDJ: Before we count, hon. The vet called, there’s six peafowl that need a home…

SD: Alastair, it’s been a pleasure chatting with you; Robert and I should probably go off-record at this point.

AG: Duly noted.

отсюда

И альпака мимими)

И альпака мимими)

Сьюзан красавица

Сьюзан красавица  Очень яркие и позитивные фотографии.

Очень яркие и позитивные фотографии.

Чувствую, будет прибавление!

Чувствую, будет прибавление!

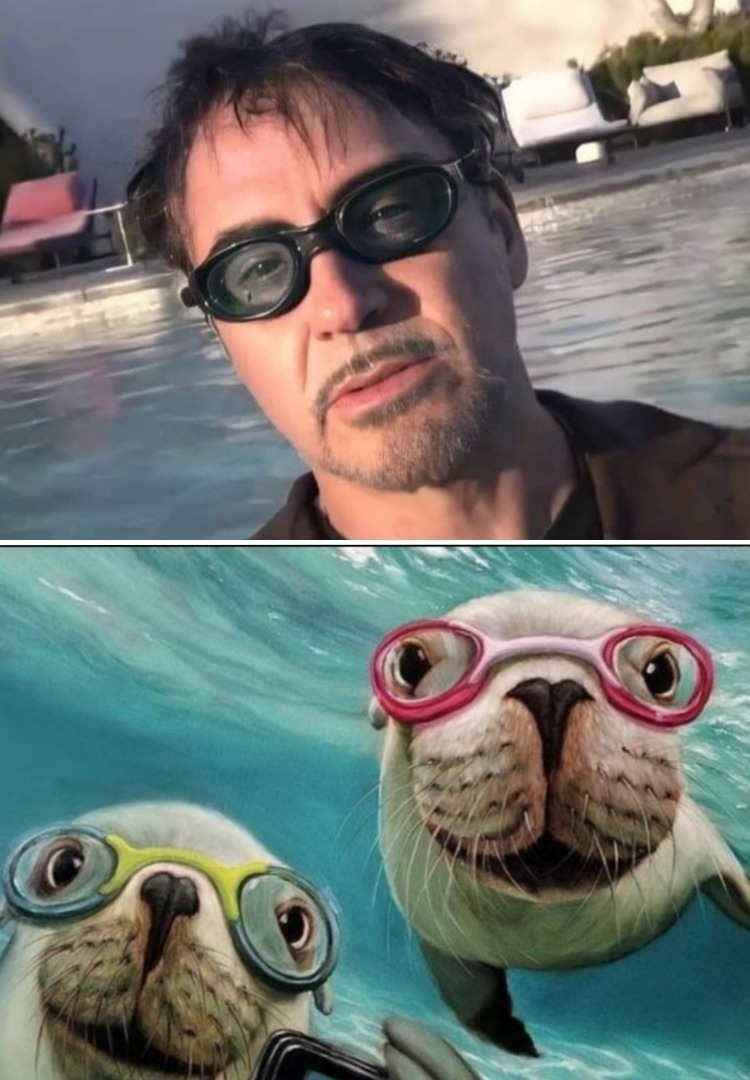

Так похоже ведь))) заплывы морских котиков. Просто у Роба там брови кажутся очень черными, это может смутить. Но на самом деле это тень от очков.

Так похоже ведь))) заплывы морских котиков. Просто у Роба там брови кажутся очень черными, это может смутить. Но на самом деле это тень от очков.